Quentin Tarantino – (Con) Artist?

Does Quentin Tarantino steal all his best ideas and present them as something new and original? And, if so, does that make him a con-man, or an artist?

Take Kill Bill (which many wrongly consider his masterpiece). The yellow suit Uma Thurman wears is lifted straight from a Bruce Lee film, Game of Death, in which (like Thurman) he rides a motorbike and has a fight in a paper house. The fight in silhouette, against the single-colour background, that’s taken from a film called Samurai Fiction, as is the idea of having a fight shot entirely in black and white. And so on, and so on. There is virtually nothing in that film which is original. It must have been easier to invent things, but no, he bravely went out there and found things to pinch. It’s a whole new kind of movie heist!

Back in 2018, The Oxford English Dictionary admitted a slew of new adjectives, taken from movie directors. Therefore Capraesque, Lynchian, Scorsesean, Spielbergian and Tarkovskian are all now officially real words. As is Tarantinoesque!

Tarantinoesque is defined as being “characterized by graphic and stylized violence, non-linear storylines, cineliterate references, satirical themes, and sharp dialogue”. It’s those ‘cineliterate references’ that we’re interested in here.

How does he get away with it?

Tarantino: Alright ramblers, let’s get rambling

I would argue that Tarantino has achieved a marketing miracle, by putting himself front and centre when it comes to selling his films. He is not a filmmaker handicapped by modesty. From day one, he has ensured that he gets interviewed at least as often as the actual stars of his movies. His latest film is a case in point – look at the advance publicity for it – does the media see this as Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt’s return to the big screen after three years off? No. It’s seen as Tarantino’s ninth film, because he’s the public face of every film he makes.

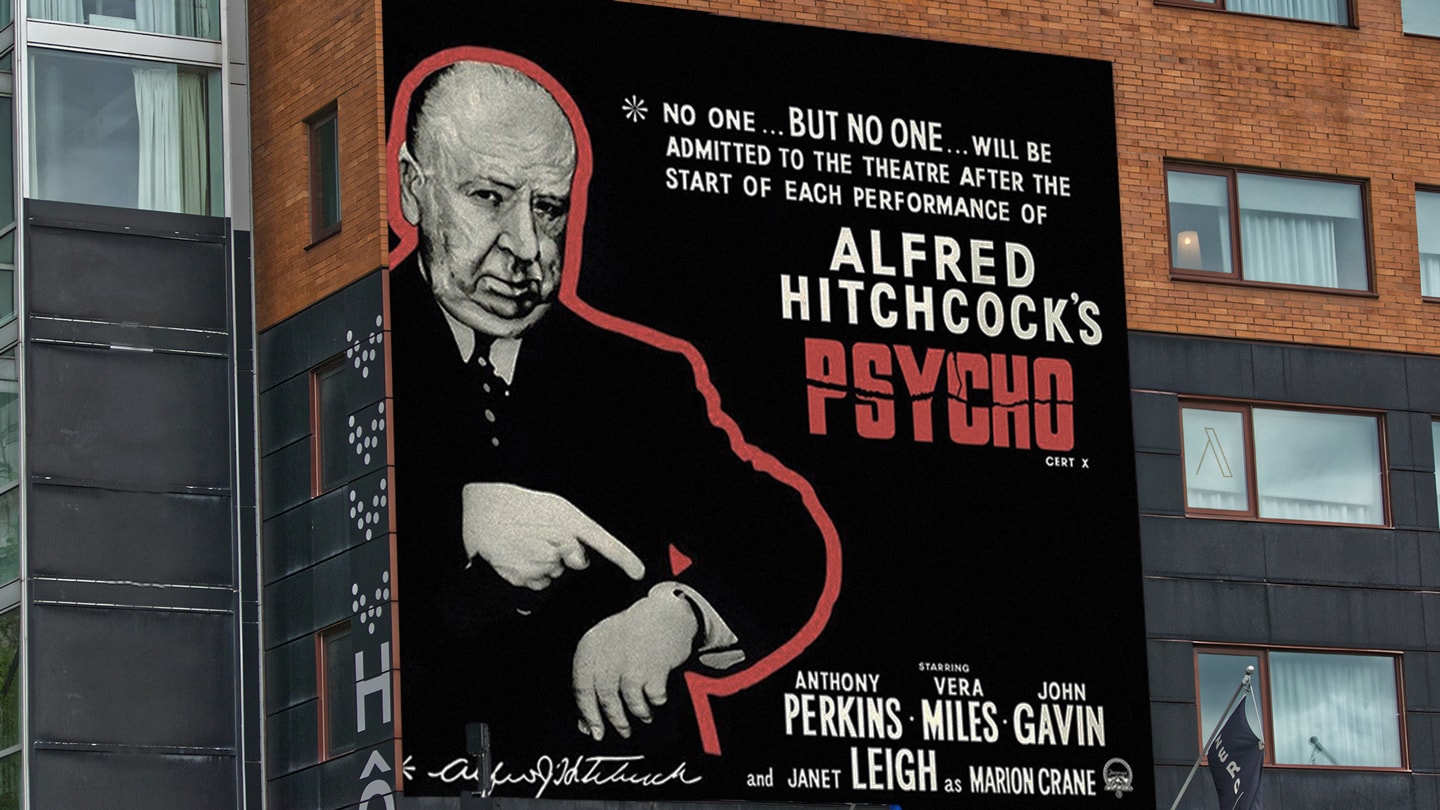

No film-maker since Alfred Hitchcock has made himself such an integral part of the marketing of his own films. And, like Tarantino, he was also a frustrated actor, who put himself in his films in cameo roles – even when he didn’t have to. This was his way of stamping his authorial signature on his films. Whichever studio he was working for, whichever stars he was working with, whichever genre he was exploring – every Hitchcock film is unmistakably a Hitchcock film. He had the perfect Hollywood Brand.

All of this is also true of Tarantino.

Since Tarantino is fond of flashbacks, let’s rewind to 1992, when his first film, Reservoir Dogs, was released. Tarantino began his campaign: He gave himself the opening line: “Let me tell you what Like A Virgin’s about” and awarded himself the possessory credit (also known as ‘the vanity credit’) of ‘A Film By’ even when his name meant nothing.

Initially, no-one cared. Few even noticed.

Tarantino: Say “what?” again

Reservoir Dogs gradually developed a cult audience in the UK, playing midnight screenings all over the country throughout 1993. At that time, the film had made more money in the UK than it had in the States – something that was almost unprecedented for an American movie.

But, even then, when – far from being in the dictionary – his name was “Quentin Who?”, there was a real sense of nostalgia in that first film. Steven Wright’s off-screen DJ introducing ‘Super Sounds of the ’70s’ set the tone.

Thing is, back in 1992, no-one was nostalgic for the ’70s. The wounds were still too fresh. Adults in America remembered the ’70s as the decade of Viet-Nam and Watergate, of disillusionment and corruption; over in the UK, we remembered the ’70s as the days of the three-day week, power-cuts and strikes. It was an awful decade, best forgotten.

The 1980s, which had only just ended, had been a deeply, desperately nostalgic decade – at least in America – but that nostalgia was for the simple days of the 1950s and early ’60s. This is what hit films like Back to the Future, Footloose and Dirty Dancing traded on, and what resurrected hit records like Wonderful World, Stand By Me, Earth Angel and Unchained Melody tapped into. The past was a safe place and we liked to hide there.

The ’70s, though? No thanks.

But Tarantino isn’t nostalgic for the things you’re nostalgic for. His taste in music almost entirely eschews the charts. His taste in movies leans toward films you, very probably, have never seen.

Tarantino ignores the obvious, mainstream icons which litter the surface of our cultural landscape. Not for him the Stranger Things method of plucking the low-hanging fruit of the labour of The Two Steves – Spielberg and King – whose impressively successful films and books defined the first half of the ’80s.

Unlike Stranger Things, or Spielberg’s own oddly onanistic odyssey Ready Player One, Tarantino doesn’t just paper the walls of his world images from the films and TV shows you grew up with – in order to generate a feel-good buzz. No, Tarantino digs deeper, excavating references which the majority of his audience won’t get. He will fill his soundtracks with deep cuts from musicians you don’t know, cast actors you’ve forgotten about, lift plotlines from foreign films you’ve never seen and mash together the signifiers of genres you don’t recognise.

Tarantino isn’t making films about your nostalgia, he’s making films about his own. His films are very personal. Only he gets all the references. That’s why he deserves the vanity credit.

He is wilfully obscurist. But, is this simply so he can steal without anyone realising there’s been a heist, or is he creating a multi-layered meta-narrative of interlocking homage and postmodern pastiche that only the cineliterate can follow?

Well, back in 1994, when he was (typically) being interviewed by all and sundry upon the release of Pulp Fiction (which actually is his masterpiece, by the way), he told Empire Magazine: “I steal from every single movie ever made … I’m taking this from this and that from that and mixing them together.” He also told Positif Magazine he sees himself as: “… a movie man who has the whole treasure of the movies to choose from and can take whatever gems I like, twist them around, give them new form, bring things together …”

This is what redeems Tarantino. He doesn’t pretend he’s coming up with something startlingly original. He has actually redefined the art of stealing art – so that ‘originality’ is now the ability to find existing stories and images people aren’t familiar with, and present them in a new way.

That’s why he isn’t stealing the work of others, he’s absorbing it into his own work. The references that fill his films aren’t just the things that he feels are cool (although that’s clearly part of it) but they relate to each other to create a depth of meaning that goes way beyond the profanity, blood-letting and curious facial hair. These are films that actually reward your reading into them.

Tarantino: That’s a bingo

Take what Tarantino does with a genre: He chooses a genre, makes a film in that genre and then fills it full of quotes from films that are already there. So, Kill Bill is a martial arts gangster movie, full of references to martial arts, samurai and gangster films from The Far East. Jackie Brown flaunts Tarantino’s love of 1970s Blaxploitation films (yes, that was a real thing) and particularly those featuring Pam Grier. Django Unchained and Hateful Eight both channel Tarantino’s enthusiasm for ‘Spaghetti Westerns’, those bizarre films made in Italy and Spain in the ‘60s, which made stars of Clint Eastwood, Charles Bronson, Lee Van Cleef and Franco Nero.

Being referenced in a Tarantino film can give a whole new lease of life to a forgotten or obscure genre. Being chosen to appear can resurrect the careers of actors and musicians whose glory days are seemingly behind them. John Travolta was very-much on the slide into straight-to-video hell, when he got the chance to play Vince Vega in Pulp Fiction. David Carradine was an almost permanent fixture in el cheapo straight-to-video movies, when he got the call for Kill Bill. Pam Grier and Robert Forster were still working, but their leading-role days were long behind them, when they got the lead roles in Jackie Brown. See, even the actors Tarantino hires bring with them a certain kind of nostalgia.

And, let us consider the masterstroke of Tarantino’s marketing strategy. He has publicly stated that he will only make ten films, then retire. His new release is his ninth full-length film – and is aggressively being marketed as such. This is a brilliant strategy, because nothing makes art more valuable than scarcity. And nothing sells as well as a limited edition.

I wonder what his tenth and final film will be? Maybe it’s time he made a proper heist film.

So, what do you think?

Is QT the five-dollar milkshake? Reach out to us on the Twitter or Facebook and let us know. Is he a maligned movie maestro, or an evil movie mastermind? And what is Like a Virgin really about?